Early Irish settlements in the colonies brought the Irish tradition of St. Patrick’s feast day to America. The first recorded St. Patrick’s Day parade was held not in Ireland but in New York City in 1762. Today, throughout the United States, millions of Irish Americans, as well as many others, come together to celebrate the established cultural identity of the shamrock clover by enjoying St. Patrick’s Day parade: anyone can be Irish for a day.

The History | A Public Identity

In order to begin a conversation that examines St. Patrick’s Day Parade as a platform that enabled the Irish community in America to construct and validate their identity, we must mention the Irish past and the changes undergone by its people as a consequence of the years predating the Great Famines of 1829 and 1849, and said famines themselves. These events provoked a massive emigration to America and as a result, the Irish immigrant community in New York and the rest of the U.S. sustained an enormous transformation: between the late 1840s and the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the old Anglo-Irish character of the pre-Famine enclave was entirely overshadowed by an emerging Irish Catholic nationalism.

Most of Irish history is an unending cycle of anarchy and rebellion against English oppression and dominance by a people attempting to protect its lands. During the pre-famine years, starting in the 1600s the Scott-Irish (individuals born in or raised on Irish soil but under Britain’s control and of Scottish descent) progressively migrated to the American colonies running from oppression and high living costs on rented land. They traveled both in groups or alone, willingly relocating and often settling in places in which they could integrate a parish that followed their beliefs; effectively profiting from a pre-established colony and moving from one Irish parish to one located in America. Mainly, but not exclusively, the Scott-Irish settled on the Eastern Coastal Area (i.g., Pennsylvania, Virginia, the Carolinas).

For their Catholic Irish counterparts, different reasons precipitated their migration into America in the late 1600s and during the 1700s: religious persecution (1695 Anti-Catholic Penal Laws) was high on the list, along with the deportation of prisoners to America, indentured servants (whom agreed to receive no pay for up to seven years in return for free passage), and the Irish slave trade. By the early nineteenth century, the Irish community in America, was a small but relatively wealthy one composed of Scottish-Irish merchants of both Catholic and Protestant origins. Thanks to their wealth and social status, the members of this mixed community were more inclined to adopt the Anglo-Saxon Protestant elements of the American elite and were able to assimilate into Anglo-American society without extreme difficulty.

However, between 1845-1849, after years of successive failed potato crops, the “Irish Potato Famine” claimed the lives of thousands of hundreds of men, women and children due to starvation worsened by the Black Pest (typhus fever). The native Irish population dropped from eight million to six million habitants and for many, migrating to America proved to be the only salvation. In the late 1840s, more than a million impoverished and unskilled Irish Catholics flowed into the port cities on the U.S’s Eastern border only to be exposed to more poverty, discrimination and segregation from a primarily Protestant host society.

They came from an entirely different world, a farming world, in which one identified oneself based on what clan, what village, and parish one belonged to; they found themselves forced to adapt to a shared urban space with Irish individuals from other towns, parishes, and counties—eventually, these distinct groups began losing their old modes of identity. This process was accelerated as commonplace hatred and appalling living conditions forced the newcomers to think of themselves as part of a single community, sharing both a common ghetto experience and being the targets of Anglo-American Protestant hatred, leading them to engage in the creation of an Irish-American form of nationalism.

I believe that the formation of a common ethnic identity can only happen when the national collective possesses shared memories. In the case of the Irish, this mechanism was deployed defensively, allowing for a shared culture to be ritually enacted and reaffirmed. Through this process their collective ethnic identity was reshaped and forged anew. St. Patrick’s Day celebration in North America constitutes the “memory-site” more than any Sunday homily ever could, because by parading, the Irish publicly showcase who they were, as well as their commitments and alliances: their community of fellow Irishmen and their pride in having served America during the independence days (the fighters of the 69th Regiment).

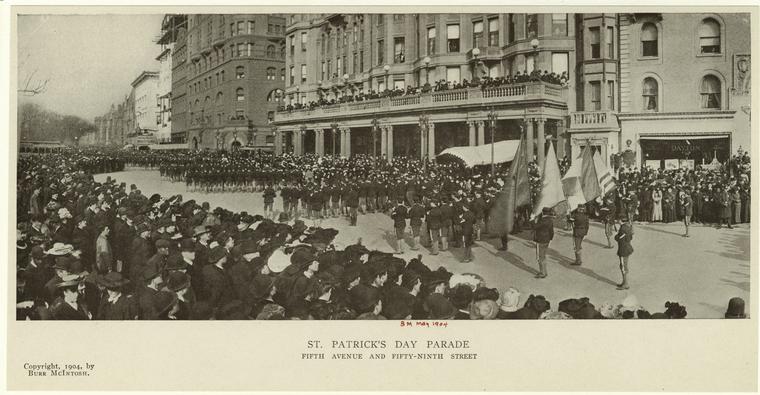

Around the 1850s, St. Patrick’s Day Parade began to be the main event in the life of Irish American communities: as Mary argued in her history of parades, the New York City, St. Patrick’s Day parade matured by changing the order of its components. Once a collection of a few militia units, benevolent societies and Catholic organizations marching with post-famine agendas, the St. Patrick’s Day Parade evolved into a nationalist display of dozens of militias, most named in honor of Ireland or in memory of various Irish heroes followed by a civic parade (fraternal and benevolent societies) escorted by militia honor guards. These societies bore banners which were rich in national symbolism; their imagery employing visual cues that were both Irish and American.

Progressively, the parade’s organization was turned over to civic fraternities manned by Irish nationals whose prime concern was to protect the image of an honorable Irish Catholic community (e.g. Ancient Order of Hibernians-AOH, St. Patrick’s Alliance of America, the Knights of Equity-KOE). Among the oldest of these assemblies is the AOH, founded at New York’s St. James Church on May 4, 1836, by men mirroring similar fraternities from Ireland, in attempts to protect the clergy and its churches from the violent attacks of American Nativists. With the arrival of the survivors of the Great Famine, the AOH opened chapters in other cities, and as the Irish Catholic movement swelled other associations like the St. Patrick’s Alliance of America (1860) and the Knights of Equity (1895) emerged.

The Ancient Order of the Hibernians in America was founded at New York’s St. James Church on May 4, 1836.

By 1870, the parade proclaimed forty thousand marchers, a far cry from 1762 when eighteen brigades of Irish soldiers serving in the British army first paraded on the streets of New York City in honor of their national patron saint: Saint Patrick.