Every year, the New York City Chinese New Year parade gathers visitors from across the four boroughs for an ethnic, joyous, and colorful celebration. Lore and tradition mingle with fireworks, lion dancing, and fast cars. Still, at the forefront of the parade is the constant reminder of the Chinese enclave’s enduring cultural heritage, its prosperity, its regional diversities, and its lasting imprint on a slice of Manhattan’s urban landscape– Chinatown blooms, celebrates, and settles back into the cadence of a strong community long after the confetti has been swept off the streets.

The Enclave | The Passing of the Dragon | Symbolism

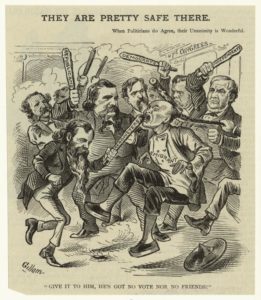

John Chinaman was the Chinese equivalent of “John Doe:” not an offensive term, initially, its widespread use began as the Chinese began to take on dangerous jobs building railroads or exploiting mine abandoned by others.

The Chinese are the oldest and largest single origin Asian ethnic group in North America, representing the third largest foreign-born group in the nation after Hispanic-Latinos (Mexicans) and Indians. Their migration happened in two waves: the first in the mid-nineteenth century and the second beginning after the 1965 and continuing to this day.

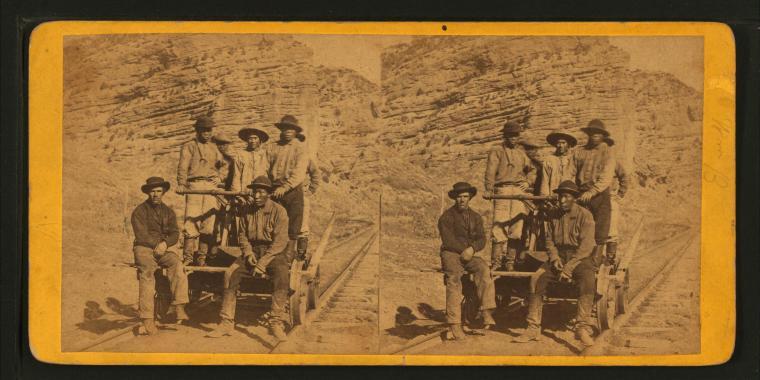

Coming from the poorest regions of Southern China (Siyi and the Pearl River Delta), the first Chinese immigrants shared a common dialect, an agrarian background, very little formal education and yet, they were connected through a clan-type social structure. Furthermore, they carried with them a common experience of exclusion within their home country as a string of civil wars, local instability, and a lack of protection from their central government taught them to rely entirely on their own resources; family ties, local clans and village associations. This first wave of these Chinese workers or “Coolies” (bitter labor) arrived through the Hawaiian plantation economy, then moved on to the Californian gold mines (1840s) and the Rocky Mountains railroad construction (1850s) as replacement for a previously dissolved black labor force. While most saw these contracts as temporary work taken on until enough money was gained for them to return home, few actually accomplished the golden dream.

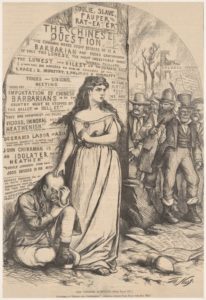

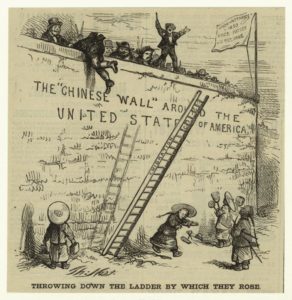

Meanwhile, the precariousness of the labor market coupled with capitalist exploitation instilled fear among the population of white workers who saw the Chinese Coolies as cunning competitors; dubbing them “the Yellow Peril.” As a consequence, labor unions mobilized and the 1870s and 1880s saw the rise of racist, anti-Chinese sentiments that brought about discrimination, exclusion and the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act; the first and only federal law ever adopted to exclude a group by nationality in the United States. Victims of discrimination and mistreatment, some Chinese immigrants returned home. However, those who were unable to return fled to metropolitan areas on both the West coast (San Francisco, Los Angeles) and the East Coast (Chicago, New York). The segregation from the mainstream job market and the unforeseen changes in accommodation established the first Chinese male ghetto-like communities in gateway cities: Chinatowns.

In New York City, ten blocks in Downtown Manhattan accommodated the majority of the city’s Chinese immigrants. This relocation offered them a common space in which they could work and talk in their own language, eat their hometown foods and protect themselves as a community against the constraints of an exclusionary host society. However, it goes without saying, that the old Chinese enclave was not the ideal setting for upward social mobility. I am inclined to agree with Portes’ argument in Zhou’s book Chinatown (1992) that the American Chinatowns were the adaptive response of an immigrant ethnic community in distress and not the result of an entrepreneurial development and that the economical outcome of the enclave was determined by a survival mentality.

A defiant Columbia protects a defenseless Chinese man from an angry Irish mob that has just burned down an orphanage. The billboard behind is full of anti-Chinese slurs.

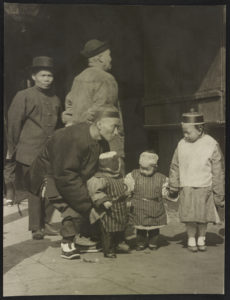

The pre-WWII New York Chinatown was a socially isolated, self-governed and self-sustained community mainly constituted of men (603 men v. 100 women); a result of the Asian Exclusion Act was the prevention of the arrival of women and the reunification of families. Also included in the Exclusion Act was the prohibition to hire Asian workers within the mainstream economy; hence, the need for Chinese men to look for jobs within their own community, as much as they did services or goods. The proliferation of laundries and food businesses awaked the need in the ethnic community to organize themselves under common cultural parameters; language being one of the most important. These ethnic organizations, more sensitive to dual-cultural problems advocated to ameliorate, advance existing and prospective resources and helped sustain culture and traditions far away from ‘home’. Throughout the Exclusion period, many clan-based ethnic associations, merchant associations (Tongs), and district associations and their underground counterparts were established. These communal organizations gained power by developing a solid social network of social capital that was able to assist the poorest and control the social and economical life of the enclave.

One of the oldest community associations is the Chinese Charitable and Benevolent Association of the City of New York (CCBA) established in 1886: historically, it has acted as a pseudo government, being called by many the unofficial ‘Mayorship of Chinatown.’

After WWII, new migration policies were put into place in the United States and the Asian Exclusion Act was repelled; effectively attempting to mend the break in the China-America relation. A second wave of Asian immigrants arrived: one with individuals of a different profile, coming not only from China but also from South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan, possessing more skills and education, as well as more financial resources. It is in this climate that the idea of a cultural parade, following the American format, came to life as a way of showcasing a distinctive culture and advertising what the enclave had to offer—Exoticism and ethnic food.

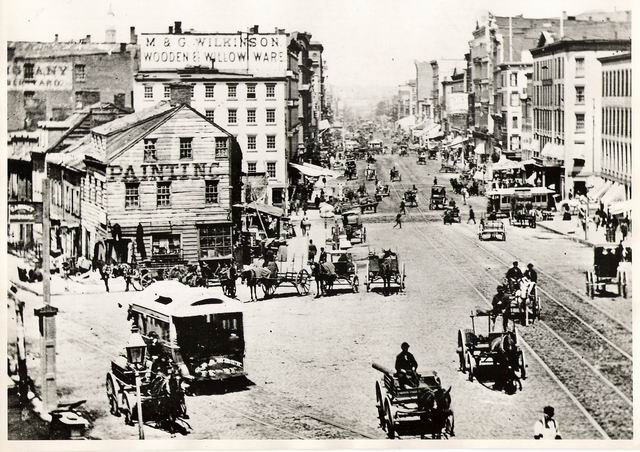

Photograph taken from Mulberry Street looking west to Canal Street.

Here, I would like to stress the value of the Chinese enclave’s social structure as the raw material for the formation and negotiation of the Chinese American ethnic identity. The enclave was not just a refuge or the center of commercial activity or a place for the propagation of cultural heritage for new Asian immigrants and their offspring. Chinatowns were historical communities where dense social ties prevailed amongst the residents; ones facing a common fate as racial minorities. It helped them remember, in the context of a hostile new society, a knowledge of themselves as integral parts of a hometown clan, a family, a neighborhood, each with its stories. This is the real core in the construction of their Chinese American identity: the urban preservation of the Chinese enclave and its cultural authenticity. Hence, the enclave reshaped the immigrants’ cultural and later political identities, beyond sociopolitical labels such as ‘yellows’, ‘immigrants’ and ‘minorities.’

Furthermore, in our modern context, in a cosmopolitan city such as New York, one under the influence of transnationalism and global market dynamics, the preservation of urban ethnic spaces like Chinatown and other historical spaces represent important acts of protection of precious diversity against the standardization that comes along with globalization. By preserving its architectural character, societal construction and cultural values, Chinatown safeguards its distinctiveness as much as the City does its soul.

It is within this urban amphitheater circumscribed by streets of tenements, stores, restaurants, and Chinese lettering, that the most important celebration of the year for the East Asian world, the Lunar New Year parade takes place. Before an enthusiastic multitude of individuals, the parade’s cultural festivities annually validate the authenticity of the group’s identity and the city’s multicultural marketplace.

Compared to the contention and reformulation of the public Irish identity (both sexual and not) that the St. Patrick’s Day parade represents, or the Italian-Americans’ steady political mobilization for the preservation and protection of their heritage symbolized by the Columbus Day parade, the Chinese New Year parade with its unique display of traditions, myths and legends is a complete and genuine reflection of the elements of the cross-cultural encounter.