The History | The Quest for Identity | Rethinking Columbus Day

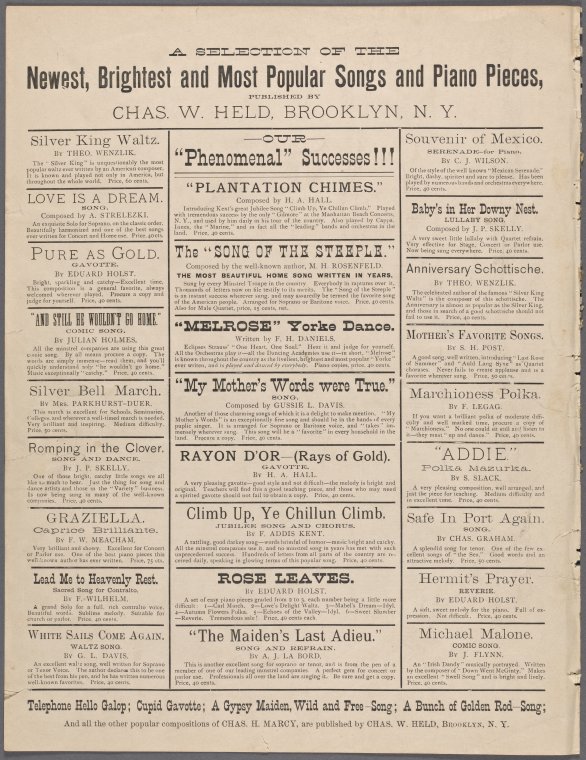

It was in the nineteenth century, at a time of post-Civil War reconstruction and creation of a new nationhood, that the American public rediscovered Columbus and his exploits. The cultural world of Columbus, selectively curated to avoid certain dark passages of the journey to discovery, was given a new shiny package and served to the American collective through the fine arts, newly minted coins, anthems, theater and monuments erected in places he never even visited. He became a role model for religious associations, cities and universities which were named in his honor, the emblem for an annual ethnic festival that has grown into a federal holiday, and the icon for the most significant World’s Fair in North America—the 1893 Chicago International World Fair.

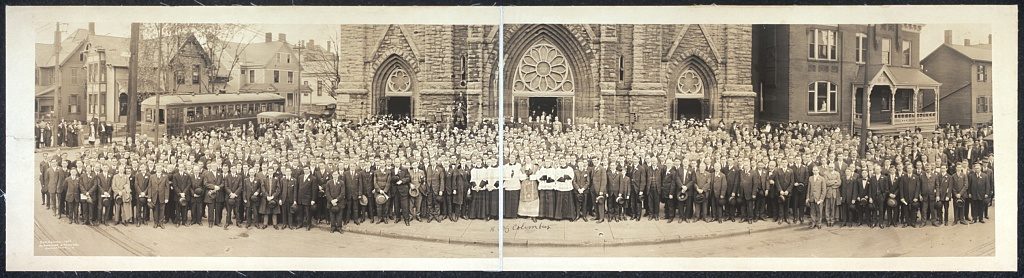

In the following decades many immigrant societies, religious fraternities, educational associations, and veterans’ organizations followed suit in making use of a conveniently romanticized ideal of the explorer in order to shape their own identities. One such Catholic fraternity worth mentioning are the “Knights of Columbus,” whom in the late nineteenth century established their organization as a response to an emerging need within their neighborhoods for a sense of community against the growing antagonism of Catholic immigrants coupled with the dangerous working conditions in factories which left many families fatherless. Thus, in 1882 the Knights of Columbus were established in Connecticut. The Knights’ recognized in Christopher Columbus their patron, the Catholic individual at the heart of the Discoverer of America. The symbol that allegiance to their country did not conflict with allegiance to their faith.

The Knights of Columbus is the world’s largest Catholic fraternal service organization. Founded by Michael J. McGivney in New Haven, Connecticut, on February 6, 1882; to advocate against the discrimination of Catholic immigrants and dangerous working conditions in factories. They were named in honor of Christopher Columbus, a symbol that allegiance to one’s country did not conflict with allegiance to one’s faith.

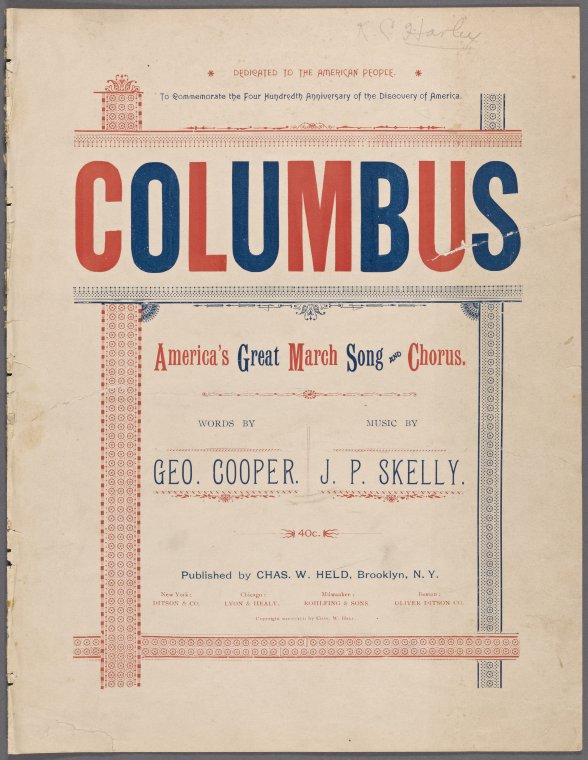

* Dedicated To The American People *

To Commemorate the Four Hundredth Anniversary of the Discovery of America

America’s Great March Song and Chorus

COLUMBUS

Still age to age shall tell the story While freedom’s flag shall o’er us wave;

Oh! still undimmed shall live in glory His noble fame, Columbus brave!

Yes, still undimmed shall live in glory, His noble fame, Columbus brave!

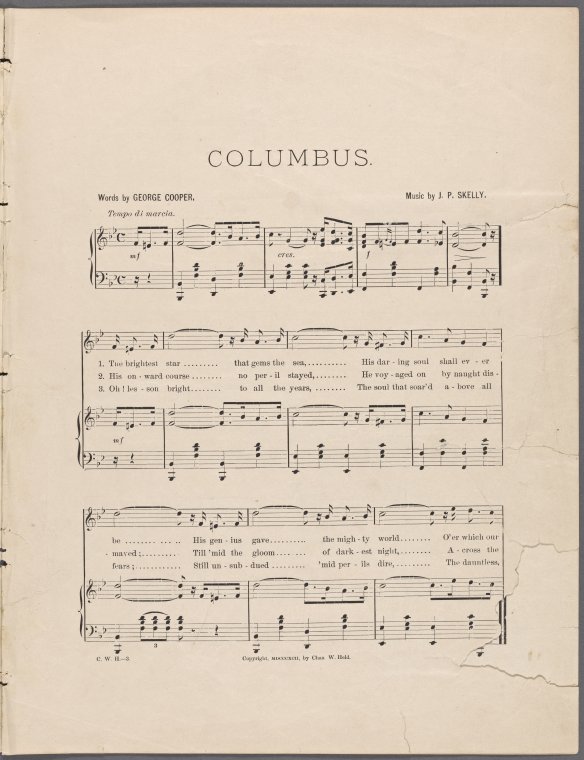

The brightest star that gems the sea, His darling soul shall ever be

His genius gave the mighty world O’er which our mighty banner is unfurled!

It is in a similar context of reshaping immigrant ethnic identities that the stigmatized immigrant Italian community took the opportunity to better their precarious station by playing a relevant role and becoming publicly visible through the use of parades and monuments dedicated to Columbus.

Example of the Italian stereotype near the end-19th century. Street Art on an old Police and Emergency Fire box. Little Italy, NY, 2017.

The end of the nineteenth century marked the beginning of Italian mass migration to North America. We speak of “Italian” mass migration but the migrants themselves perceived their identities to be regional rather than national; they came from different regions carrying with them distinctive traditions, food and religious affiliations—they were separate. Progressively, with the end of the first World War and the beginning of the second World War and due to engrained ethnic prejudice, work discrimination and bigotry, the prevalent “Italian” stereotype was that of an inferior, illiterate and violent resident. As a response to this overwhelmingly ignorant consensus and in order to stand up for their rights and successfully compete with other immigrant communities, first and second generation immigrants endeavored to embrace a communal “Italian” national identity regardless of their ancestors’ regional affiliations. The Italianization of the Columbus ideal in the United States served the Americanization of Italian Americans well: on the Quadricentennial of the discovery of America, while the United States celebrated Columbus’ achievements, Italian Americans seized their moment.

Local associations came together during religious festivities, like Columbus Day, in order to raise funds that were then used to erect several monuments celebrating Columbus, like the Central Park statue and the Columbus Circle square; this collective and inter-city effort helped them develop a cohesive group identity, one that stressed Columbus’ Italian origins, validated their right as equals in their adopted country, and increased their visibility. For Italian-Americans, Columbus Day represents their legacy: the recognition of a monumental historical event led by a fellow Italian that brought about unification and pride in an ostracizing period of rampant anti-Italianism. Therefore, the Columbus Day celebrations and parade served as an undeniable platform and aid for a stigmatized Italian-immigrant identity rather than as a showcase of cultural diversity.